The Way Out of Suffering

In the quest for freedom from suffering, two prominent Buddhist traditions offer distinct yet complementary approaches: the Mahayana and Vipassana traditions. Both are rooted in the Buddha’s teachings and aim at reaching a state of lasting peace and liberation, yet they provide different pathways for understanding and addressing the root causes of human dissatisfaction.

Mahayana Tradition

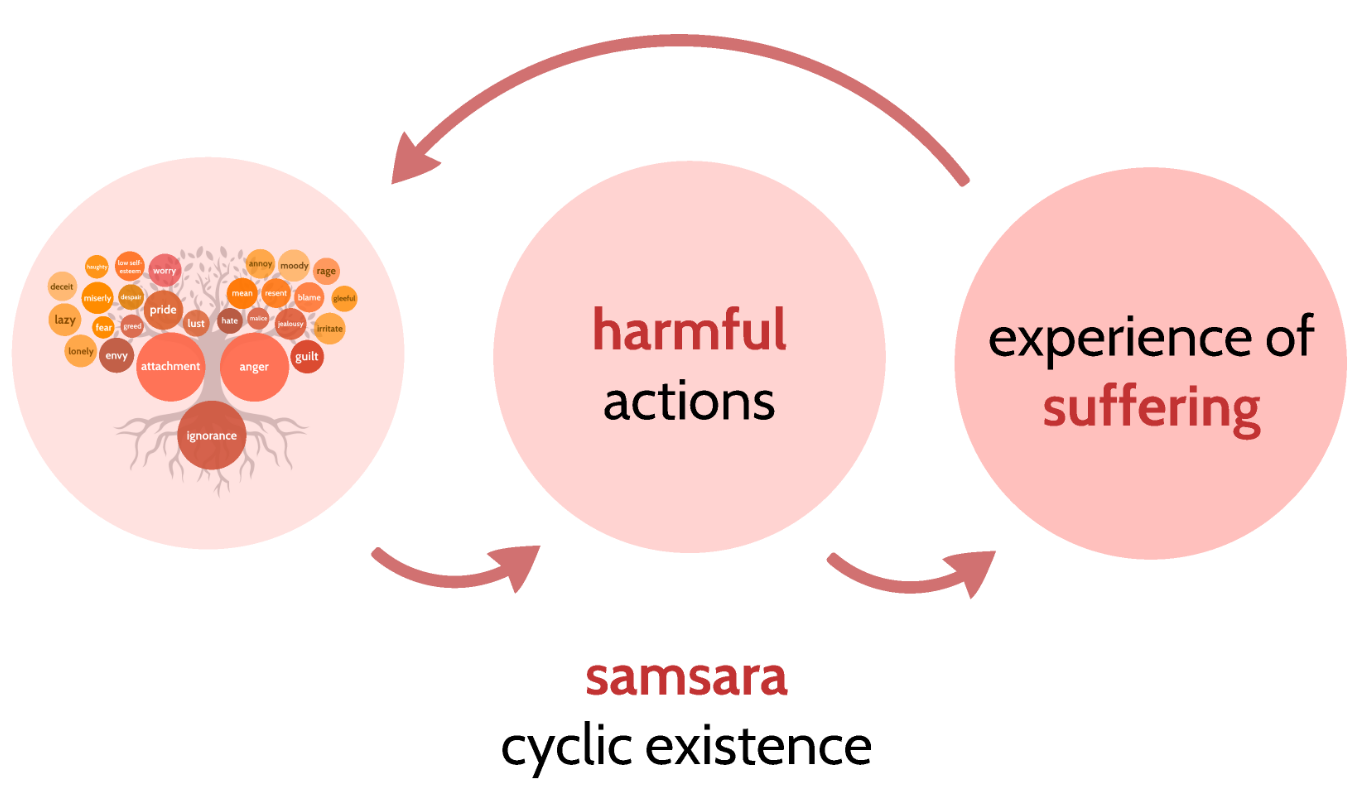

As we’ve previously discussed, suffering (or dissatisfaction) pervades our lives. The Buddha realized that the root of our suffering lies within our own minds, not in external circumstances. Specifically, suffering arises from mental afflictions or delusions, with the fundamental delusion being ignorance. From ignorance, attachment and anger develop, as well as many other mental defilements, such as pride, fear, resentment, jealousy and so on.

Image credit : Thubten Wangdu

These delusions distort our perception of reality and cloud our minds. In response, we engage in unwholesome actions of body, speech, and mind, which accumulate negative karma. These harmful actions, in turn, perpetuate our misery, trapping us in the cycle of suffering known as Samsara.

Image credit : Thubten Wangdu

To break free from this endless cycle of suffering, it is essential to address the problem at its root: ignorance. Ignorance is overcome by cultivating wisdom, a quality that allows us to see reality as it is, free from the mental constructs that obscure our minds. The mental afflictions of attachment and anger are counteracted by the virtuous qualities of loving-kindness and patience, respectively. Together, wisdom, loving-kindness, and patience form the Three Antidotes to the Three Poisons. From them stems all the other virtuous qualities, such as humility, generosity, forgiveness, tolerance and so on.

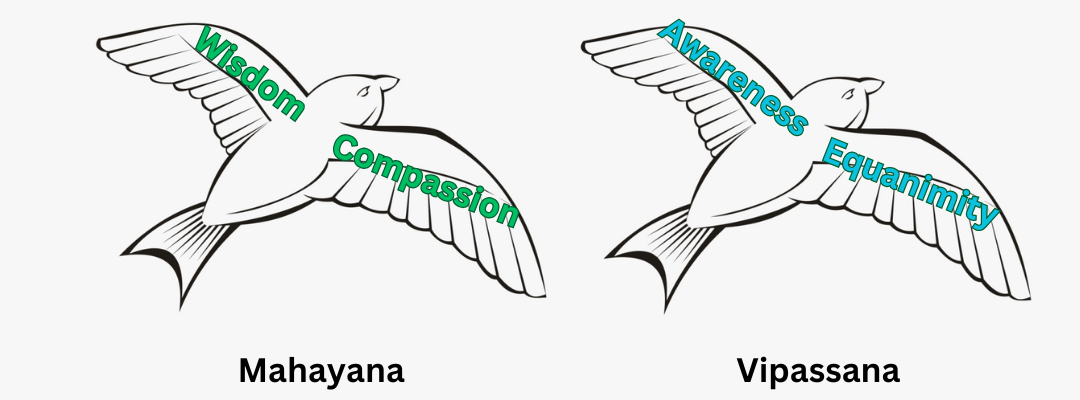

Image credit : Thubten Wangdu

In order to eliminate our delusions and cultivate these virtues, the Buddha presented a practical method known as the Noble Eightfold Path. In the Mahayana tradition, this approach is presented as the Six Perfections. The Six Perfections emphasize the cultivation of the two essential aspects of Buddhism: wisdom and compassion. Just as a bird requires two wings of equal strength to fly, a Buddhist practitioner needs both wisdom and compassion to progress toward enlightenment. When our delusions are replaced by virtuous qualities, we only execute positive actions, breaking the cycle of suffering.

Image credit : Thubten Wangdu

Vipassana Tradition

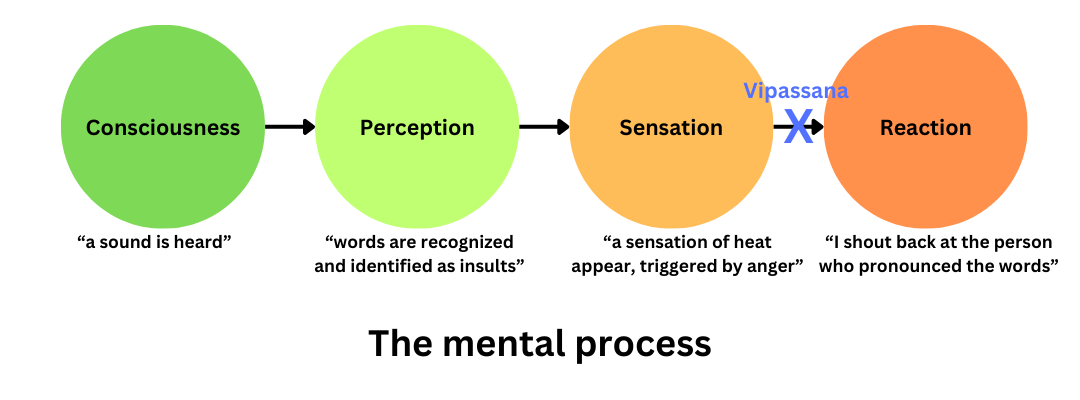

The Vipassana tradition, as taught by S. N. Goenka, offers a different approach to freeing oneself from the cycle of suffering. In this tradition, the mind’s process is understood in four distinct stages:

- Consciousness: The mind first registers sensory input, simply becoming aware of what is happening (e.g., realizing that a sound has occurred).

- Perception: Next, the mind recognizes and evaluates the sensory input based on past experiences and memory, labeling it as either good or bad (e.g., interpreting the sound as words and identifying them as praise or insults).

- Sensation: After the evaluation, corresponding sensations arise in the body—either pleasant or unpleasant—based on the mind’s judgment (e.g., a feeling of heat in the abdomen, triggered by anger).

- Reaction: Finally, the mind reacts to these sensations with either craving or aversion (e.g., shouting back at the person who made the remark).

These reactions to sensory experiences are called Sankharas. The strength and frequency of these reactions create habit patterns, which lead to automatic tendencies and reinforce mental conditioning. Over time, these patterns take root deep in the mind, perpetuating the cycle of suffering and misery.

The goal of the Vipassana technique is to break the link between sensations and reactions in the mental process. This is achieved by observing physical sensations in the body without reacting, which helps develop two essential qualities:

- Awareness: The capacity of observing sensations.

- Equanimity: The ability refrain from reacting with craving or aversion.

Understanding that these sensations are impermanent (e.g., the sensation of pain will eventually fade) helps us realize that there is no benefit in clinging to pleasant sensations or feeling aversion toward unpleasant ones.

This practical method trains the mind to stop reacting to sensations with craving or aversion. This process eliminates accumulated Sankharas and preventes new ones from forming, gradually purifying the mind. When the mind is completely free from all Sankharas, one reaches a state of pure happiness and lasting peace : the liberation.

The two wings for flying out of suffering.

DISCLAIMER : The information shared in this article are based on my personal experience from various Buddhist courses I attended in India and Nepal. I am not by any means an expert on the subject. If you notice any inaccuracies, please feel free to contact me or mention them in the comments.