How to use Nonviolent Communication

Nonviolent Communication (NVC), developed by psychologist Marshall Rosenberg, is a communication technique that encourages empathy and honesty in interactions. It helps you to express yourself clearly while listening to others with respect—even in difficult conversations. NVC shifts communication from blame and criticism to mutual understanding, by reducing escalating arguments and promoting more harmonious connections.

Article adapted from Dave Bailey.

“We are dangerous when we are not conscious of our responsibility for how we behave, think, and feel.”

― Marshall B. Rosenberg, Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life

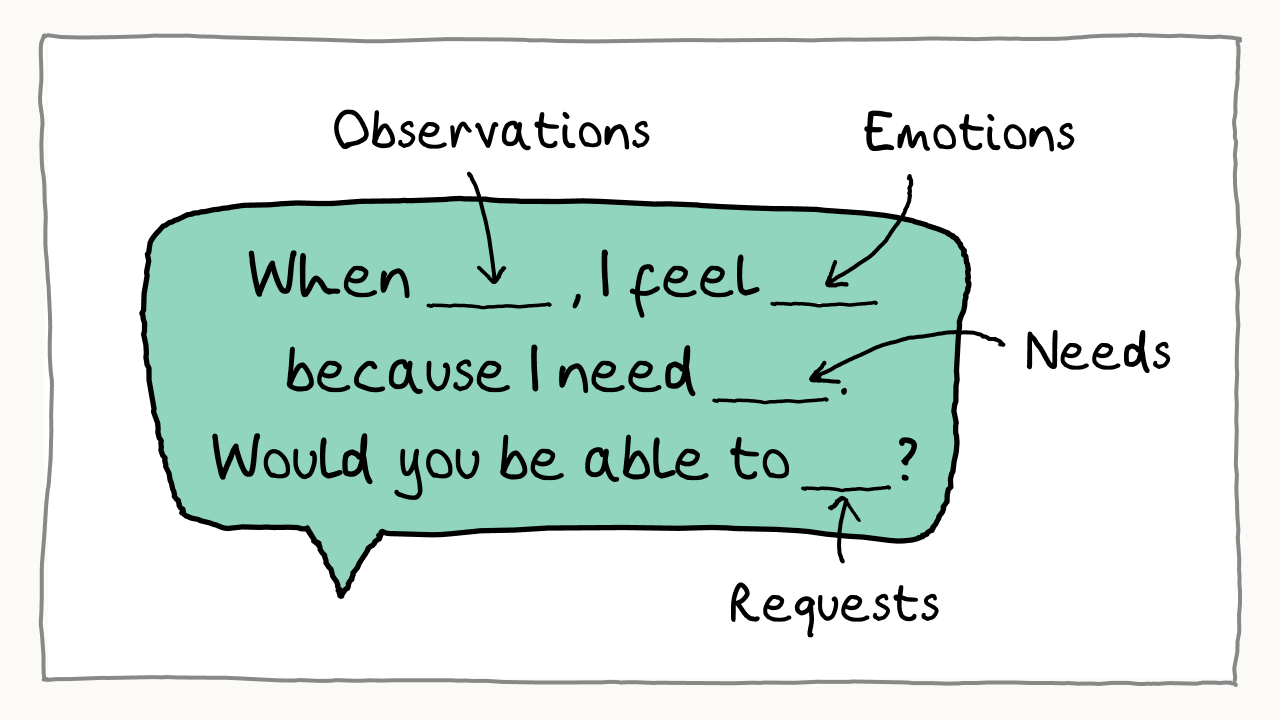

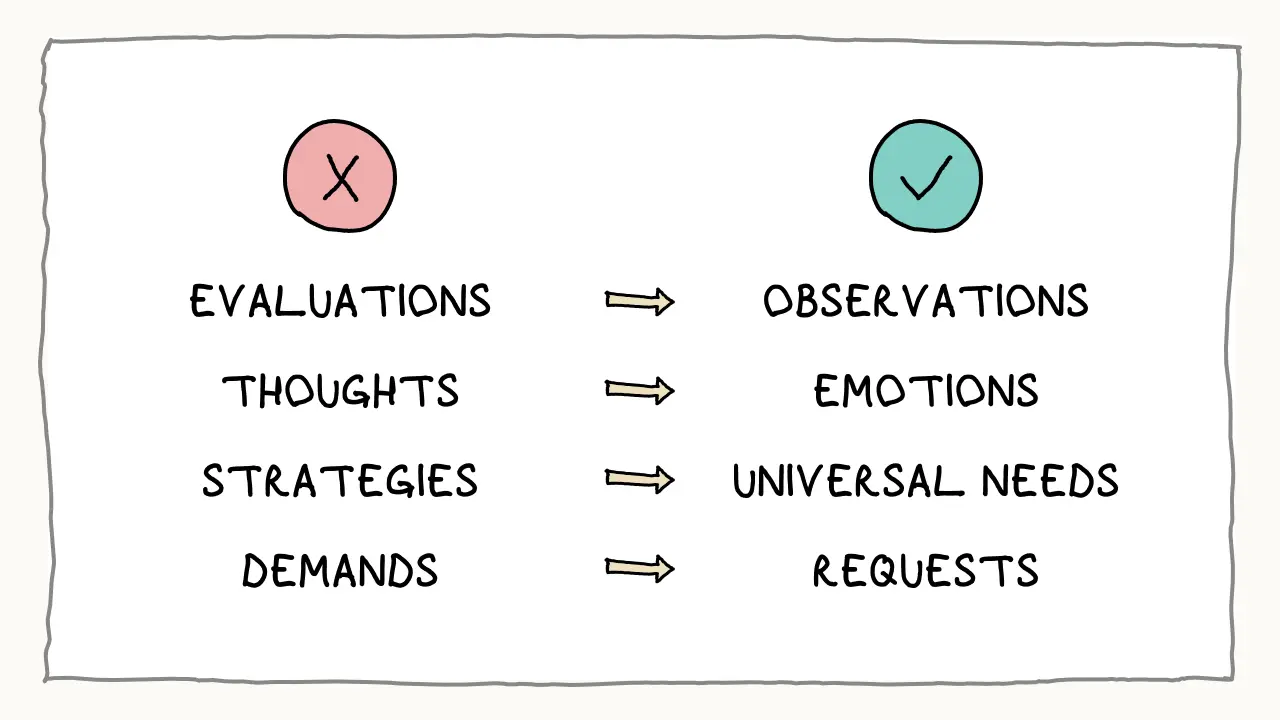

At the core of NVC is a straightforward communication pattern composed of 4 key elements:

This pattern seems easy, but applying it in real life situations is surprisingly challenging. NVC makes some subtle but critical distinctions:

Understanding these nuances is key to handling difficult conversations. Let’s go through each of the four components step-by-step.

1. Observations vs. Evaluations

“The ability to observe without evaluating is the highest form of intelligence.”

―Jiddu Krishnamurti

The first step consists in stating facts without judgment.

An observation is something that you actually saw or heard in the past. You can think of it as raw information. The majority of observations fall into two categories: (i) what you heard, e.g., direct quotes, and (ii) what you saw, e.g., visible past behaviours.

Our brains are hardwired to take raw information and instantly make up a simple story — good or bad, right or wrong, hero or villain. These stories are evaluations and they are very hard to separate from observations.

Here are a few examples to illustrate the difference:

| Evaluation ❌ | Observation ✅ |

|---|---|

| ‘You are lazy.’ (a character attack) | ‘You said that you’d send the document last week and I haven’t received it.’ |

| ‘Your work is sloppy.’ (a criticism) | ‘Three of the numbers in the report were inaccurate.’ |

| ‘You’re always late.’ (a generalisation) | ‘You arrived ten minutes late to the meeting this morning.’ |

| ‘You ignored me.’ (implied intent) | ‘I sent you two emails and I haven’t received a response.’ |

An easy way to check whether you’ve made an observation or an evaluation is to ask yourself, ‘What did I actually see or hear?’

2. Emotions vs. Thoughts

Being aware of our emotions and being able to communicate them to others is key to healthy communication. Expanding your emotional vocabulary and deepening self-awareness can significantly enhance how you connect with yourself and others. Have a look at this post to improve your emotional literacy by learning what words you can use to express emotions, with more nuances than “I feel good” or “I feel bad”.

Some common words people use to describe how they feel during a difficult conversation are:

- Scared

- Annoyed

- Anxious

- Confused

- Embarrassed

- Hurt

- Sad

- Tired

The choice of words we use is important because often, what comes after ‘I feel,’ isn’t an emotion — it’s a thought. Compare the following example:

| Thought ❌ | Emotion ✅ |

|---|---|

| ‘I feel that you aren’t taking this seriously.’ | ‘I feel frustrated.’ |

If you can substitute ‘I feel’ with ‘I think’ and the phrase still works, it’s a thought, not an emotion. And sharing our thoughts in difficult conversations can often get us into trouble, especially if the other person disagrees and wants to correct you.

There are a few emotions that require extra attention and curiosity before sharing them:

Anger

Anger often masks more painful emotions like hurt and shame. It’s important to figure out what’s underneath the anger before having a difficult conversation, because when you’re angry, you’re more likely to speak impulsively and forget NVC altogether.

Evaluative words (faux feelings)

Some words are confused as feelings when they are interpretations or assessments of others’ actions.

Consider the phrase, ‘I feel blamed’. Doesn’t it sound a lot like the evaluation, ‘You blamed me’? To reduce the chance of a defensive response like, ‘I didn’t blame you’, NVC asks that you identify the evaluation and recognise how it impacts you emotionally. For example, feeling ‘blamed’ might leave you feeling ‘scared’. Here are some others:

| Evaluation ❌ | Impact ✅ |

|---|---|

| ‘I feel judged.’ | ‘I feel resentful.’ |

| ‘I feel misunderstood.’ | ‘I feel frustrated.’ |

| ‘I feel rejected.’ | ‘I feel hurt.’ |

A list of faux feelings can be found on this post.

3. Universal Needs vs. Strategies

Nonviolent communication asserts that all human beings share the same universal needs and that behind every negative emotion lies an unmet universal needs. For example, if a certain comment left you feeling embarrassed, you might realise that you felt embarrassed because your need for consideration wasn’t being met. The pairing of emotions with universal needs has a transformative effect in difficult conversations.

Common universal needs that come up a lot in difficult conversations are:

- Autonomy

- Collaboration

- Consistency

- Connection

- Clarity

- Empathy

- Integrity

- Recognition

- Respect

- Reassurance

- Security

- Support

- Understanding

A more exhaustive list of universal human needs can be found on this post.

Not everything that follows the words, ‘I need’ is a universal need. NVC distinguishes between our universal needs and the strategies that would meet our needs. You can say, ‘I need a sandwich,’ but that doesn’t mean sandwiches are a universal need. Eating a sandwich is a strategy to meet your need for nourishment.

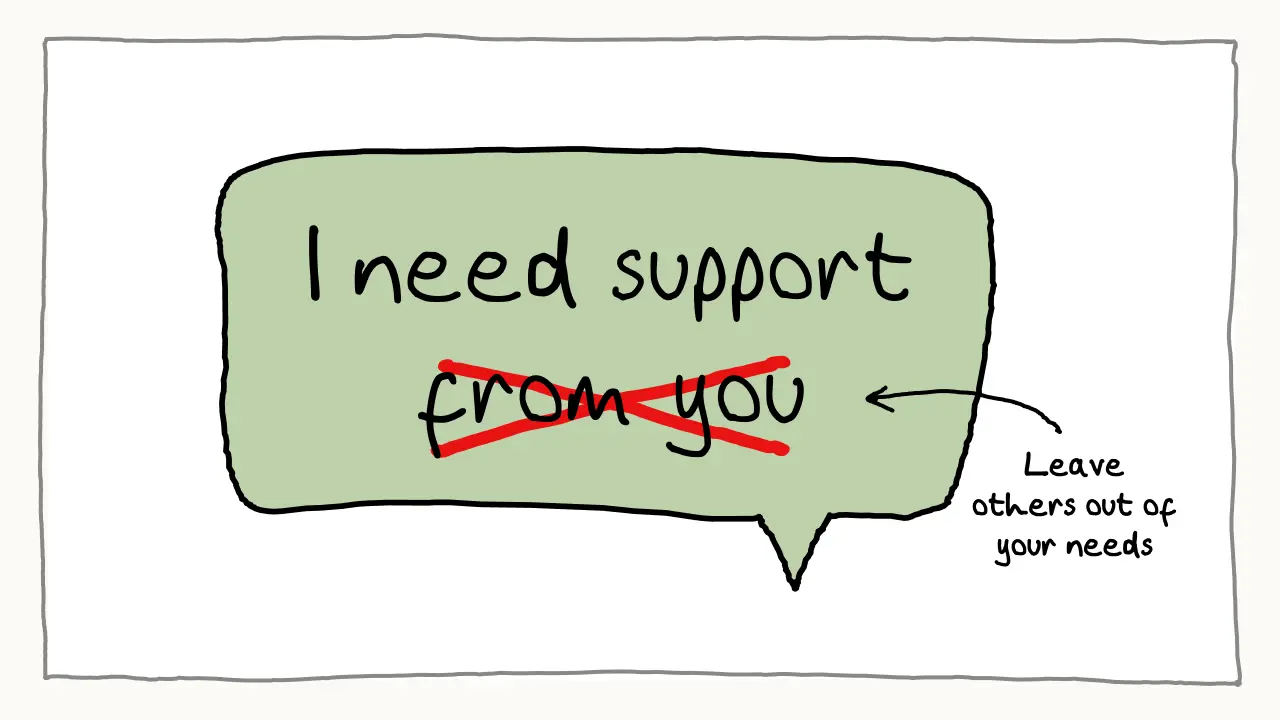

There’s a subtle but important point to make here. As soon as you include ‘from you’ in the need statement, it stops being universal. When I say ‘I need support from you’, it can be easily interpreted as a veiled accusation, i.e. it implies that ‘You aren’t supporting me’. To minimise the chance of defensiveness, NVC tells us to leave other people out of our needs.

Here are some examples to express your needs and not using it as a manipulation strategy:

| Strategy ❌ | Universal need ✅ |

|---|---|

| ‘I need you to copy me into every email.’ | ‘I need some transparency.’ |

| ‘I need support from you.’ | ‘I need support.’ |

4. Requests vs. Demands

The last stage of the NVC process is to formulate a clear, actionable request, but not a demand. What is the difference between a request and a demand? Both are strategies that would meet an unmet need. But unlike demands, requests are invitations for the other person to meet our needs… but only if it isn’t in conflict with one of their needs.

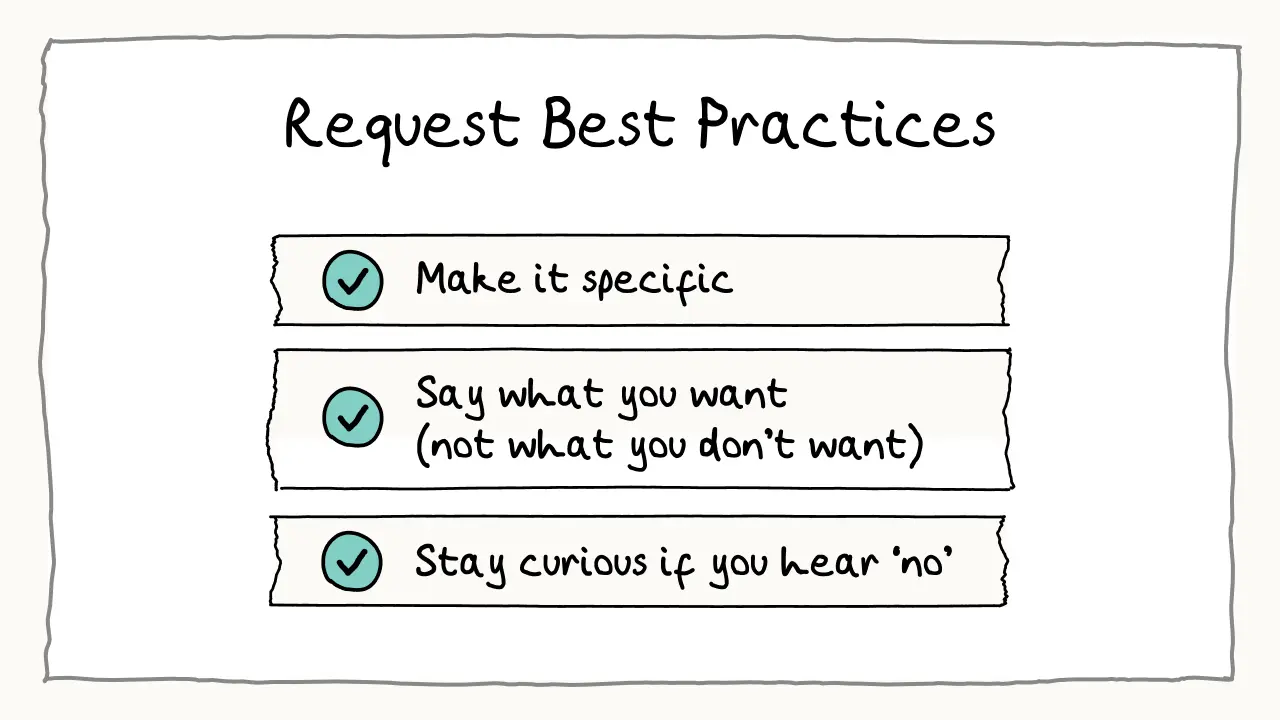

There are three principles that can help you make clear requests:

a) Make it specific

‘I request that you be more respectful,’ is vague — what signals respect to you may not signal respect to someone else. Spell out the concrete behaviours that would meet your need for respect: ‘I request that you arrive at meetings on time.’

b) Say what you want, not what you don’t want

‘I request that you don’t dismiss other people’s ideas straightaway,’ explains what you don’t want, but it doesn’t spell out what you do want. Take time to clarify the behaviours you want to see. For example: ‘I request that when a team member shares an idea, you ask two or three probing questions before sharing your conclusion.’

c) Stay curious

There are many ways to satisfy your underlying needs, but is there a way of satisfying everybody’s needs? To maximise the chance of having your needs met, treat ‘no’ as an invitation to explore the needs stopping someone from saying ‘yes’.

Remember, great communication isn’t just about what you say, it’s about what other people hear. Even something as simple as, ‘I’d like you to be on time for the next meeting,’ can have an unintended meaning, depending on the context.

Don’t be afraid to check in and ask someone to recap what they heard. You don’t want to patronise them, so be diplomatic and politely ask, ‘Just so we know we’re on the same page, could you play back what I’m asking of you?’

Examples

During difficult conversations, it’s important to be extremely concise. Aim to describe your observations, feelings, needs and requests in less than 40 words. Using more words suggests you’re justifying your needs, and this decreases their power.

It’s also worth noting the importance of having these conversations face-to-face. NVC loses some of its power when it’s in an email.

Here are some examples of NVC in action.

- ‘When you said, “I’m not happy with your work,” to me in front of the team, I felt embarrassed because it didn’t meet my need for trust and recognition. Please, could we set up a weekly one-on-one session to share feedback in private?’

- ‘I haven’t received any responses from the last three monthly updates. I’m feeling concerned because I need input. Please, would you mind getting back to me with responses to my questions in the last update?’

- ‘You arrived 10 minutes late to the last three team meetings. I am frustrated because, as a team, we have a need for efficiency. Please, could you help me understand what’s happening?’

All this preparation for 30–40 words may sound like a lot of work. It is a lot of work. But the result is clear, concise and powerful. No naming and shaming. No waffling. Just clarity about what you’ve observed, how you feel about it, and what needs are not being met. And at the end, you have a clear, actionable request.

Key Takeaways

- NVC is a practical framework for expressing needs and resolving conflict with empathy.

- It breaks down communication into four components: observations, emotions, universal needs, and requests.

- Using NVC can help people have difficult conversations without criticism or defensiveness.

- Emotional literacy and understanding your own needs are foundational to successful NVC.