The different Buddhist Traditions

Entering the world of Buddhism can be confusing, as there are many different traditions out there. However, it’s important to understand that the Buddha did not intend to create a new religion with a fixed doctrine. In fact, during his lifetime, he made it clear that his intention was not to teach a rigid system of beliefs, but rather to show a path that individuals could follow for their own personal development.

The Buddha recognized that each person is unique, with different capacities and preferences, so he did not establish a single, unchanging doctrine for everyone to follow. Instead, he encouraged people to explore and find the practices that best suited their own journey.

As a result, individuals must eventually decide for themselves which teachings to follow and how to interpret them. This flexibility has led to the development of various Buddhist traditions that are practiced today.

This post aims to provide a simple overview of the similarities and differences among the major Buddhist traditions and schools that exist today.

The Three Vehicles

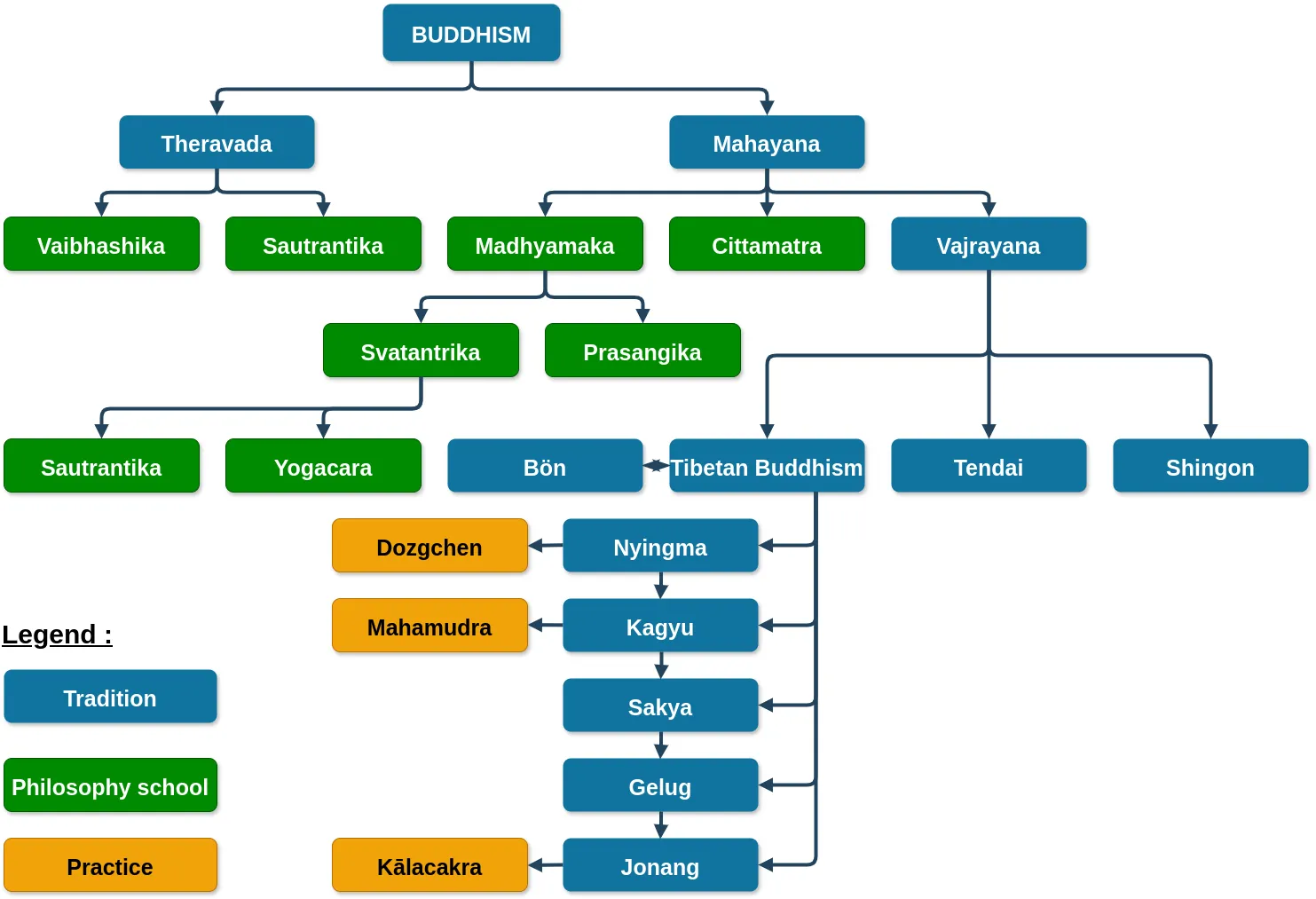

The various forms of Buddhism are known as Yana, a Sanskrit word meaning “path” or “vehicle.” Each Yana represents a vehicle for crossing the ocean of Samsara and reaching the shore of Enlightenment. Buddhism recognizes three main vehicles: Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana. While each of these paths has its own unique characteristics, customs, and practices, they all share the core teachings of the Buddha.

The term Hinayana (“lesser vehicle”) is considered pejorative and should be replaced by Theravada (“Way of the Elders”). Vajrayana, meanwhile, is a specialized subset of the Mahayana tradition.

Theravada : The Way of the Elders

Theravada is the oldest of the three main Buddhist traditions, emerging shortly after the Buddha’s death. It is considered the most conservative branch of Buddhism, with its teachings primarily based on the Pali Canon, an ancient text in the Pali language that contains the Buddha’s original teachings.

The core of Theravada Buddhism revolves around foundational principles such as the Four Noble Truths, the Three Jewels, and key concepts like impermanence, non-self, karma, rebirth, and dependent origination, along with ethical precepts. Followers of Theravada aim to achieve liberation through the Noble Eightfold Path.

This tradition emphasizes renunciation and self-purification through personal meditation and spiritual practice, particularly through samatha (calm abiding) and vipassana (insight). The spiritual ideal in Theravada is the arahant or “accomplished one,” who attains nirvana—liberation from the suffering of samsara (worldly existence)—through solitary effort. The ultimate goal of Theravada practice is individual awakening, achieved gradually over multiple lifetimes of practice and dedication.

Theravada is the predominant form of Buddhism practiced in countries such as Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos.

Mahayana : The Great Vehicle

Mahayana is the largest Buddhist tradition in the world, founded in India around the 4th century CE. While it builds upon the teachings of Theravada, Mahayana places greater emphasis on compassion and selflessness.

Mahayana Buddhists aspire to become bodhisattvas—beings who seek enlightenment not only for themselves but to help others achieve liberation. Unlike Theravada, Mahayana practitioners venerate multiple Buddhas and bodhisattvas and often engage in rituals and devotional practices such as chanting.

A key teaching in Mahayana is that all beings inherently possess buddhanature—the seed of awakening. By perfecting the qualities of a Buddha, one can overcome obstacles to enlightenment, potentially even within a single lifetime.

Central to Mahayana philosophy is the concept of emptiness (Shunyata)—the understanding that all beings and phenomena lack inherent existence and arise only through interdependence. The doctrine of the “two truths” explains that the everyday world of appearances (relative or conventional reality) and absolute reality (emptiness) are not separate, but one.

Mahayana is the dominant form of Buddhism in East and Central Asia, flourishing in countries like China (Chan Buddhism), Japan (Zen, Nichiren, and Pure Land Buddhism), Vietnam (Thien Buddhism), and Korea (Seon Buddhism).

Vajrayana : The Diamond Vehicle

Vajrayana, also known as Tantric Buddhism, Tantrayana, or Mantrayana, is an offshoot of Mahayana Buddhism. It centers around esoteric rituals and practices, known as tantras, designed to lead practitioners to enlightenment. These practices include visualization, mantra recitation, and tantric yoga. Vajrayana is renowned for its swift and powerful methods of achieving awakening, and it is considered the fastest path to enlightenment, with the potential for realization within a single lifetime.

While Vajrayana upholds the Mahayana bodhisattva ideal, its pantheon is more extensive, including fierce protector deities and dakinis (female deities). A central practice is deity yoga, in which practitioners take on the identity of a chosen deity embodying enlightened qualities. This practice is guided by a guru, or lama, a master who initiates the student into these esoteric practices. Rituals play a significant role in Vajrayana, including the repetition of mantras (sacred syllables and verses), visualization of mandalas (sacred diagrams), sacred hand gestures (mudras), and prostrations. Before advancing to higher tantric practices, practitioners must complete Ngondro, a set of preliminary practices. The highest practices involve the symbolic union of feminine (wisdom) and masculine (compassion) principles.

Tantric practices are often kept secret to protect the sanctity of the teachings and safeguard practitioners from energies they are not yet trained to handle.

The Vajrayana tradition originated in northern India around the 5th century CE, took root in Tibet in the 7th and 8th centuries, and later spread across the Himalayan region. Today, most Vajrayana practitioners are Tibetan Buddhists, though tantric Buddhism also exists in Japan, particularly within the Shingon and Tendai traditions.

Bön is an indigenous religious tradition of Tibet that shares many similarities with Tibetan Buddhism. Tibetan Buddhism itself is divided into four main schools, each with its unique focus and practices.

The oldest school is the Nyingma tradition, founded by Padmasambhava (also known as Guru Rinpoche). Nyingma places special emphasis on Dzogchen (“The Great Perfection”), which represents the pinnacle of teachings and spiritual achievement.

The Kagyu school, founded by Milarepa, is known for its focus on direct experience of enlightenment rather than intellectual study alone. A central practice in this school is Mahamudra, a meditation technique aimed at directly realizing the nature of the mind. Practitioners follow a progressive series of meditative techniques, guided by a qualified teacher, to uncover ultimate truth.

The Sakya school, founded by Khön Könchok Gyalpo, is closely associated with the Hevajra-tantra, a text on non-dualism. Sakya emphasizes systematic scholarly study, ritual practices, and the transmission of wisdom within a familial lineage to preserve the purity of its traditions.

The Gelug school, founded by Tsongkhapa, is the newest and now the largest school of Tibetan Buddhism. It is characterized by a strong focus on monastic discipline and rigorous philosophical study, aimed at cultivating a virtuous and ethical life.

In addition, the Jonang school, founded by Yumo Mikyo Dorje, is known for its practice of the Kālacakra Tantra (Wheel of Time) and its unique philosophical perspective called “zhentong,” which offers a distinct understanding of mind and reality.

Summary

Below is a summary table comparing the three vehicle : Theravada, Mahayana and Vajrayana.

| Theravada | Mahayana | Vajrayana | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Name meaning | Way of the Elders | Great Vehicle | Diamond Vehicle |

| Founded | 1st century B.C.E | 4th century CE | 5th century CE |

| How to deal with the 3 poisons | avoid the poison | take the antidote | distil the poison to its pure essence |

| Location | Southern India, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos | China, Japan, Vietnam, Central Asia, Korea | Tibet, Nepal, Northern India, Bhutan, Mongolia, Himalayas region |

| Goal | attain Nirvana through personal meditation and solitary efforts | reach enlightenment by practicing widsom and compassion | reach enlightenment as fast as possible using esoteric practices |

| Spiritual ideal | Arahant | Boddhissattva | Boddhissattva |

Four philosophical schools

The doctrine of the Two Truths is a fundamental concept in Buddhist philosophy. It teaches that there are two ways to perceive reality:

- Conventional truth : relative existence, how things appear to be.

- Ultimate truth: absolute existence, how things truly are.

Relative or conventional truth refers to the reality we experience in everyday life—concrete objects and phenomena such as cars, people, sickness, and death. These conventional objects exist, but their existence depends on various conditions.

Ultimate truth, on the other hand, is inexpressible and beyond ordinary experience. It is empty (sunya), non-dual, and free from concrete characteristics. It lies beyond the limits of conventional thought and language.

Both truths are simultaneously valid and, in fact, are one and the same. Conventional truth is a manifestation of ultimate truth, while ultimate truth forms the fundamental basis of conventional reality.

However, there are differences in how the doctrine of the Two Truths is interpreted, which has led to the development of four main schools of Buddhist philosophy.

In the Theravada tradition, there are two primary philosophical systems:

- Vaibhashika (The Great Exposition School) asserts the existence of truly established external objects but denies the existence of self-knowers (consciousness that knows itself).

- Sautrantika (The Sutra School) accepts both external objects and self-knowers.

Within the Mahayana tradition, there are two major schools of thought:

- Madhyamaka (The Middle Way School) does not assert the true establishment of anything, not even conventionally. It is divided into two branches:

- Svatantrika (The Middle Way Autonomy School) accepts autonomous reasoning but denies true establishment, even conventionally. It has two sub-schools:

- Sautrantika-Svatantrika (Sutra-based Middle Way Autonomists), whose views align with the Sautrantika school of the Theravada tradition.

- Yogacara-Svatantrika (Yogic Middle Way Autonomists), whose views align with the Cittamatra (Mind-Only) school.

- Prasangika (The Middle Way Consequence School) is a more radical branch of Madhyamaka that refutes even autonomous reasoning, relying solely on deconstructive logic to reveal the emptiness of all phenomena.

- Svatantrika (The Middle Way Autonomy School) accepts autonomous reasoning but denies true establishment, even conventionally. It has two sub-schools:

- The Cittamatra (Mind-Only School) asserts that external objects do not exist; only the mind exists. However, it does accept the existence of truly established self-knowers.

I hope you’re keeping up—Buddhists certainly love organization! Below is a diagram summarizing the various traditions, schools, and practices in Buddhism.

Further reading

DISCLAIMER : The information shared in this article are based on my personal experience from various Buddhist courses I attended in India and Nepal. I am not by any means an expert on the subject. If you notice any inaccuracies, please feel free to contact me or mention them in the comments.